| CNN TRAVELLER - ISSUE 4 - 2003 | English

|

||||||||

|

Bridge over troubled waters - by Alison Appelbe A perfect stone bridge is once again rising over the emerald-green Neretva River, in the city of Mostar in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Construction of an exact replica of what was a much-admired 427-year-old pedestrian passageway destroyed during the recent Balkan War—and often referred to as "a crescent moon in stone"—is nearing completion. When the new Stari Most ("old bridge") opens in July, it will represent one of the most complex and important restoration projects in the world today. Strongly endorsed by the people of Mostar, a city of 120,000 in the south of the country, the project is also seen as a symbol of Muslim, Serb and Croat reunification.

This narrow bridge that was for centuries the pride of the town and a meeting place for people of every ethnicity—even the site from which prospective bridegrooms dove 20 metres into the fast-moving river to demonstrate their worthiness—will reconnect the Croat and Muslim neighbourhoods that, before the war, co-existed relatively peacefully. Stari Most was designed by Turkish architect Mimar Hajrudin for Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, and completed in 1566. Arching steeply over a vigorous river that flows from the mountains nearer Sarajevo into the Adriatic Sea, the bridge was a link on the road between the Ottoman East and Christian West. More importantly, it was the hub of a town that developed around it, and a Turkish masterpiece. "It is one of the most beautiful bridges in the world," wrote Rebecca West in her travelogue of Yugoslavia, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, in the late 1930s. "A slender arch lies between two round towers, its parapet bent in a shallow angle in the centre." "The stone rose of Herzegovina" and "a cradle of poets and wise men" rhapsodized Muslim writers of a structure that served as the centrepiece for a richly textured Muslim quarter of cobble lanes, mosques and minarets, red-tile-roofed houses and bazaars. Solidly built, Stari Most withstood earthquakes, floods, and dozens of battles over the centuries. However, the most recent Balkan war proved its undoing. In 1991, the span—30 metres across and 20 metres above the water—took a few hits from Serbian gunners. Despite attempts by Muslims to protect it by draping it with tires and makeshift scaffolding, the bridge continued to sustain damage as Croats who live (along with some Muslims) on the city's west bank, fired towards the predominantly Muslim sector on the east. Then on Nov. 9, 1993, while hard-line Croat nationalists laid siege to the Muslim quarter, more than 50 artillery shells fired from Croat positions brought it down. At the time, Serbian architect and former mayor of Belgrade, Bogdan Bogdanovic, told the New York Times: "A person simply loses the sense of himself at times like this. It was like a heavenly arch. It had nobility, a kind of élan. I ask myself how the people of Mostar will live without that bridge. They have now lost a part of their being." Says architect Manfredo Romeo, who with a team from the Italian firm of General Engineering and the engineering department of the University of Florence, headed by Andrea Vignoli, designed the new-old bridge: "This was clearly and attack on the cultural identity of a community on one hand, and a world cultural heritage on the other. Attacks like this happened all over Bosnia, and particularly Mostar—from both sides. It was a loss that cancelled the link to a place, and to the past. Now we're recovering it." In 1995, Hungarian engineers with the NATO-led Stabilization Force (SFOR) in Bosnia-Herzegovina, pulled the first slabs of stone from the river bed. Between 1997 and 1998 the Italian team, using digital imaging software called Galileo Siscam Technology, contributed to a larger UNESCO plan, headed by architect Carlo Blasi, for rebuilding the surrounding neighbourhood of StariGrad. The bridge design followed in 2001.

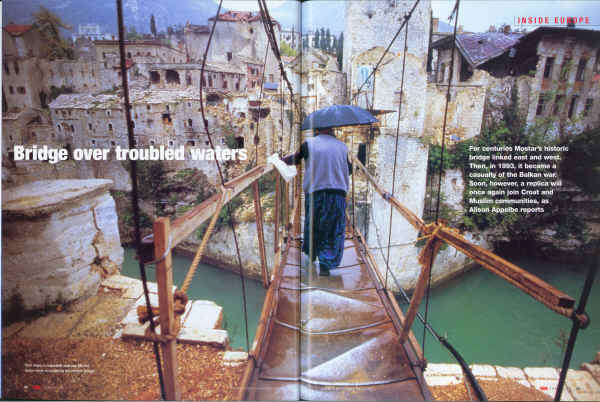

The bridge has been built by Turks employed by the Turkish construction firm of ER-BU, whose blue banner hangs over the worksite. A Croatian architect, Zelico Pekovic, has supervised reconstruction. Funders include UNESCO, which had nominated Stari Most for World Heritage Site status before its destruction, the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Italy, France, The Netherlands, Turkey and Croatia. The project has been co-ordinated by the City of Mostar (Project Co-ordination Unit or PCU), and has involved an "international committee of experts" (ICE), as well as German, French, Turkish, Bosnian and Croatian engineering firms. In the early days of the project, the wisdom of creating a replica of Stari Most was hotly debated. But in the end, the people of Mostar—seeing its absence as both an aesthetic loss and reproach to inter-ethnic strife—supported rebuilding the bridge just as it was. "You cannot understand the design of the Old Bridge if you do not know what it meant to the people of Mostar," Romeo says. "Its shapes were not strictly linked to any era, style or fashion. It had few devices and no ornamental element: its beauty and value were to be found in its simplicity and functionality." The team considered reusing what stones could be salvaged, but found most too fractured or weakened by natural forces. But it studied them—particularly the voussoirs that form the arch, and square blocks called ashlars that create the bridge facing—and how they fit together. It considered no fewer that 45,000 pieces of data on the cut of the stones alone. Identical light-coloured limestone, called tenelija, was quarried from the same site as that of the original. And the new bridge has been assembled as was its forebear—using cramps, dowels and melted lead. Only the mortar, in keeping with modern safety and structural requirements, was of a different makeup. The Turkish masons and labourers were expected, even encouraged, to put their own, subtle stamp on their work. "Small variations are part of the beauty of the monument, and shouldn't be neglected," Romeo says. "But a system of progressive controls have made sure that we are not going far from the final design and the former bridge. "The new bridge, as a copy, will not have the same value or meaning as the old one," Romeo adds. "But it will be a way to remember the tragic war and, by recreating the entire complex, the memory, cultural identity and symbol of the people." Today, the final touches are being put on the bridge and towers, called Tara and Halebija, and formerly a powder magazine and guard room respectively. By summer, the temporary walkway across the Neretva—almost always busy with onlookers—will come down, and 22 structures of the $15.5 million Stari-Most project will open to the public.

But that won't be the end of the Mostar Project. Romeo and his colleagues are planning a Mostar Museum (the inevitable MoMu), to house the relics of "the real Old Bridge," record and celebrate both bridges, along with the history of Mostar itself. The museum has the support of the city, UNESCO, World Bank, and the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, which is rebuilding other parts of the city. Says Romeo of an attraction he hopes will become a Bilbao-inspired tourist draw: "If we forsake those ruins, then we will fail in the project for the rehabilitation of the bridge. The museum will represent the completion of the Old Bridge project, and demonstrate that different groups can be enriched and unified by culture and architecture." For the time being, the people of Mostar ("Mostari" meaning keeper of the bridge) are looking forward to the return of a beloved image. "This project should bring peace and co-existence, and foster tourism," says PCU director Rusmir Cisic. "The Old Bridge will become again the symbol of the city of Mostar throughout the world."

|

|||||||||

|

CREDITS: Alison Appelbe - Canadian freelance writer SOURCE: CNN Traveller - Travel the World with CNN - ISSUE 4 - 2003 |

|||||||||